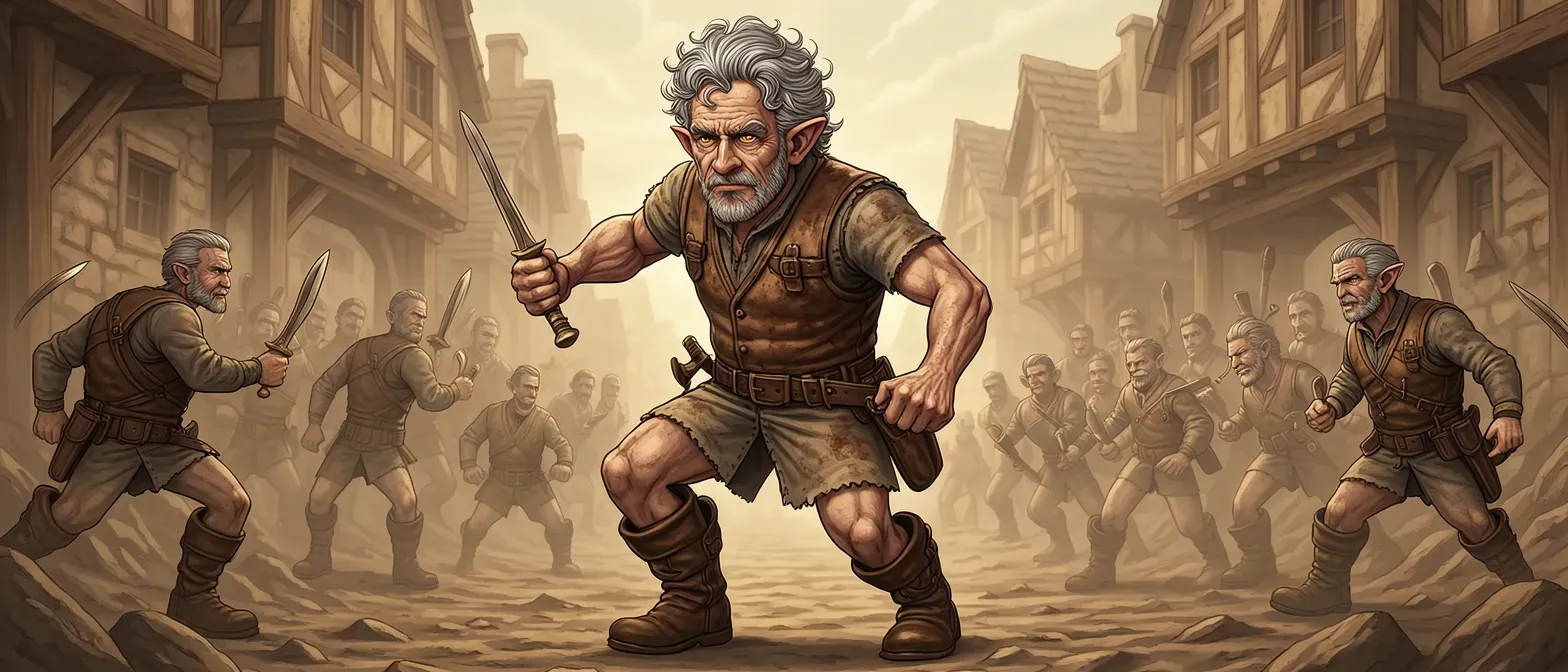

Whorf was a gnome of middling years, perhaps sixty summers under the earth's unyielding weight, though his kind aged like stubborn roots, slow and unyielding. He stood no taller than a man's knee, with a frame wiry as a miner's pickaxe handle, skin etched with the fine lines of dust and shadow from decades in the deep veins of the Ironspike Mountains. His hair, a wild mop of iron-gray curls, was perpetually dusted with coal grit, and his eyes—sharp, hazel flecks like flecks of pyrite—missed nothing in the flickering lantern light of Grimholt, the ramshackle town carved into the mountainside where miners clawed fortune from stone. He wore a patched leather jerkin over a woolen shirt stained by lamp oil and sweat, trousers tucked into stout boots cobbled from old harness leather, and a tool belt slung low on his hips, bristling with hammers, chisels, and a coiled rope that had seen better days. A brass badge, dented and tarnished, pinned to his chest marked him as town guard, though his hands, callused and ink-stained from sketching repair plans, spoke more truly of his handyman soul.

In Grimholt, where the air hung heavy with the tang of sulfur and the rumble of collapsing shafts echoed like distant thunder, Whorf had carved a life from necessity. Orphaned young in a cave-in that claimed his clan, he arrived as a wide-eyed lad, apprenticed to the forge-master until his nimble fingers proved better suited to mending barricades than swinging hammers. He wanted nothing more than a secure vein of ore to call his own—a small claim, enough to build a workshop above ground, away from the choking dark, where he could tinker with gears and pulleys to ease the miners' burdens. But the mountains were cruel mistresses, riddled with unstable faults and greedy overseers who hoarded the richest lodes for the cartels from the lowlands. Whorf's patrols uncovered sabotage—rival crews dynamiting supports to flood competitors' tunnels—and his fixes bought time, but never peace. The why of it gnawed at him: the earth itself seemed to conspire, shifting with malice, while men above ground schemed for profit over lives.

Undeterred, Whorf turned inventor in the shadows of his cramped guard shack, a lean-to of scrap timber wedged against the saloon. He rigged tripwires from bellwire and counterweights from ore scraps, patrolled with a crossbow modified for gnome grip—its bolts tipped with his alchemical brews to mark intruders without killing. It worked because he knew the mountain's moods better than any dwarf surveyor; the groans of stone were his lullabies, the drip of water his clock. Miners whispered of 'Whorf's Whisper,' the unseen guardian who mended a jammed lift at midnight or warned of gas pockets with uncanny precision. Yet conflicts shadowed him: a bitter feud with the foreman, who saw his meddling as thievery of labor; the ghost of his lost family in every collapse; and the creeping rheumatism in his joints, a reminder that even gnomes couldn't outrun the grind. In the end, as a great tremor shook Grimholt and the cartel abandoned the dying town, Whorf's final contraption—a vast pulley system—evacuated the survivors, claiming his claim in the form of grateful lives saved. He limped into the dawn light, workshop unbuilt but legacy etched in the mountain's scars, a handyman hero who bent the unbendable to his will.