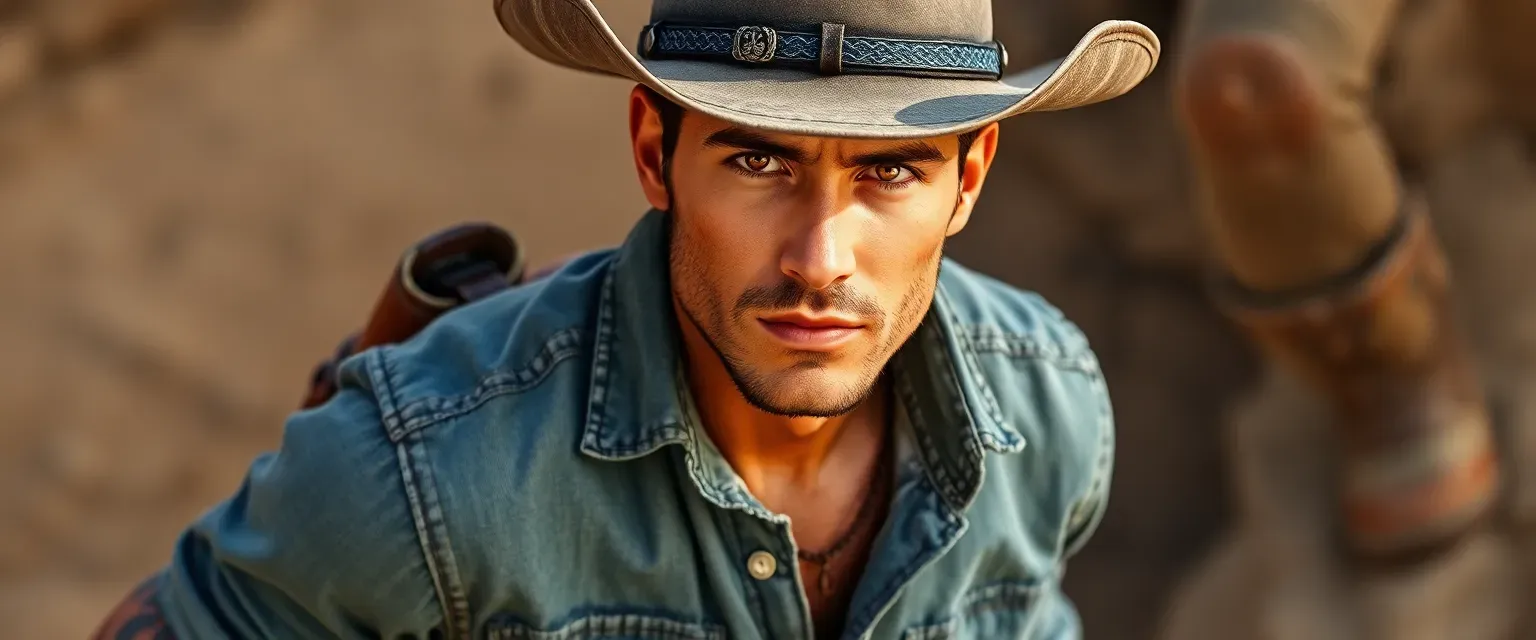

John Archer stood a head taller than most men in the dusty border towns of the American Southwest, his frame lean and wiry like a mesquite tree weathered by relentless sun and sandstorms. At thirty-four years old, his face was etched with the harsh lines of a life spent chasing horizons that never quite delivered, his skin tanned to leather by years under the unrelenting sky. His eyes, a piercing hazel that caught the light like polished flint, peered out from beneath the brim of a battered Stetson hat, its crown faded from black to a mottled gray. He wore a faded denim shirt, sleeves rolled up to reveal forearms corded with muscle and scarred from knife fights and barbed wire, tucked into trousers patched at the knees, held up by a belt with a silver buckle shaped like a coiled rattlesnake—a trophy from a long-ago duel in Tucson. His boots, scuffed and caked with the red dust of the trail, bore the marks of countless miles, and around his neck hung a locket containing a faded tintype of a woman with soft eyes, a ghost from his past he rarely spoke of.

Born in the shadow of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains during the waning days of the Civil War, John had grown up in a world where the line between lawman and outlaw blurred like heat haze on the prairie. His father, a Confederate veteran turned rancher, taught him to shoot before he could read, instilling in him a fierce independence and a distrust of distant governments that meddled in men's affairs. But it was the raid that shaped him—a band of Comanche warriors sweeping through their homestead one bloody dawn, leaving John as the sole survivor at fifteen. He wanted nothing more than to reclaim the life stolen from him: a patch of land, a family, stability in a land that chewed up dreams and spat out bones. Yet the frontier conspired against him; every claim he staked was contested by greedy speculators or haunted by memories that turned the soil sour. Droughts withered his crops, rustlers stole his cattle, and the law, corrupt as a politician's promise, always seemed one step behind justice.

John's response was to become a bounty hunter, tracking men who preyed on the weak, his Colt Peacemaker an extension of his unyielding will. He moved like a shadow across the badlands, his unique quirk a soft, rhythmic whistling of old folk tunes—'Shenandoah' or 'The Yellow Rose of Texas'—that echoed eerily through canyons, unnerving foes before he even drew iron. It was this melody that masked his approach during a showdown in Deadwood Gulch, where he cornered Black-Eyed Pete, a notorious train robber who'd murdered his kin years back. Pete's gang scattered at the sound, mistaking it for a banshee's wail, allowing John to pick them off one by one with shots as precise as a surgeon's scalpel. It worked because John understood the land's whispers—the way wind carried sound, how fear amplified the unknown—and turned them into weapons sharper than any blade.

But victory was fleeting. The bounty brought coin enough for a fresh start, yet in the quiet nights, the whistling turned mournful, a lament for the boy he'd buried under that New Mexico sky. Conflicts gnawed at him: the bottle that dulled the ghosts but eroded his aim, the allure of easy money from shady deals that tempted his moral compass, and the woman in Silver City who offered love but demanded he hang up his guns—a choice between the fire of vengeance and the warmth of hearth. In the end, as the railroads tamed the wilds and towns sprouted like weeds, John rode into the sunset toward the Pacific, land bought with blood money, whistling a tune of uncertain hope. He was no hero in ballads, just a tall man wrestling demons in a dying world, his arc bending toward redemption not through glory, but the stubborn grit that kept him moving when lesser souls would have broken.